Cooperative Dynamics and Interfacial Scales in Glass Forming Liquids

Ultra-thin polymer films and polymer nanocomposites have ubiquitous technological applications, ranging from electronic devices to artificial tissues. These nanoconfined polymer materials, typically with thickness less than 100 nm, exhibit properties that are different from their bulk counterparts. To engineer the dynamics, e.g. glass transition temperature $T_g$, remains a technological challange because lack of fundamental understanding of glass formations in polymer melts under naoconfinements.

This research was part of my undergraduate thesis work under supervison of Prof. Francis Starr at the Physics Department, Wesleyan University. You can find my thesis here . We studied glassy and cooperative dyanmics of glass forming liquids under nanoconfinements using molecular dynamics. There are three significant findings:

- We developed a unifying framework connecting string-like cooperative motions and relaxation time [1-3].

- We established a direct relation between dynamical interfacial scales and the strings (and so the relaxation time) [1, 2].

- We developed a theory connecting the long relaxation time and the Debye-Waller factor which characterizes the dyanmics at a short time scale [4].

Free volume idea and dynamical interfacial scales

|

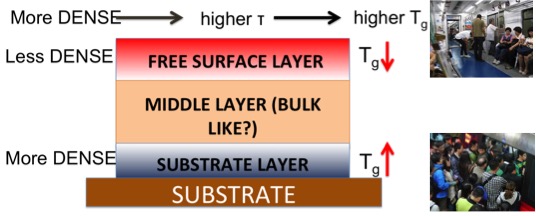

Have you ever stucked in a over crowded train during the rush hour? In this situation, it will take much longer time for everyone to move around inside the train. This simple explanation is oftend used to describe glass formation in polymer melts. In thin films, the dynamics (relaxation time $\tau$) accross the film will be different due to local surrounding. Close to free-surface, atoms can freely move while atoms near the substrate may be either mobile or immobile depending on the surface attraction. It turns out that the perturbed regions grow with decreasing temperature, and thus these effects become signifcant for thinner films. We called these growing perturbing regions “interfacial scales” $\xi$. The next question is how do we quantity this regions, dynamically or based on structure (e.g density)? Our further investigations [3] revealed that the dynamical scales grow much faster than the the static scales. This was the first hint of connection between relaxation time and interfacial scales.

Unifying theory describing dynamics based on string-like motions and interfacial scales

|

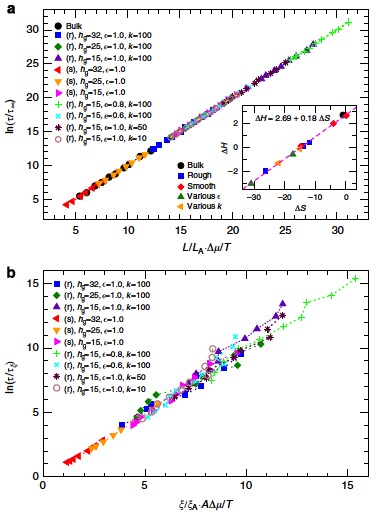

Back to our the analogy of moving in a overcrowded train, we can only move if our neighbors are also moving. This means in order to move you have to move cooperatively. In polymer melt, the atoms are moving in string-like fashion. Adam-Gibbs (AG) envisioned that there is an intrinsic scales that govern the relxation. We then found that the dynamics can be described by a simple relationship

\[\tau_s(T)=\tau_{\infty}{ \rm exp}\bigg[\frac{L(T)}{L(T_{\rm A})}{\frac{\Delta \mu}{k_{\rm B}T}}\bigg],\]where $\Delta \mu$ is the limiting activation free energy at elevated temperatures, $\tau_s$ has Arrhenius dependence, $L$ is the string length. $L_A$ is the string length at Arrehenius temperature. $\Delta \mu$ is expected to contain both the enthalpic $\Delta H$ and entropic terms $\Delta S$, so that $ \Delta \mu = \Delta H - T \Delta S$. This relationship is universal, in a sense that it is applicable to thin films with different surface architectures (e.g surface roughness and different interaction strengths) and also polymer nanocomposites [5].

Further we found that the dynamical interfacial scale is proportional to the string length . And thus, the dynamics are also can be described by the interfacial scales [1]. This finding is significant because meausring string-length with high-accuracry in experiments remains a great challange. The interfacial scale, on the other hand, is experimentally accessible as it can be obtained by measuring the dynamics locally.

To be continued

References:

[1] P. Z. Hanakata, J. F. Douglas, F. W. Starr, Nature Communications, 5, 4163 (2014).

[2] P. Z. Hanakata, B. A. P. Betancourt, J. F. Douglas, F. W. Starr, The Journal of Chem. Phys., 142, 234907 (2015).

[3] P. Z. Hanakata, J. F. Douglas, F. W. Starr, The Journal of Chem. Phys., 137, 244901 (2012).

[4] B. A. P. Betancourt, P. Z. Hanakata, J. F. Douglas, F. W. Starr, PNAS, 12, 2966 (2015).

[5] B. A. P. Betancourt, J. F. Douglas, F. W. Starr, Soft Matter, 9, 241 (2013).